“Should a happiness machine be something you can carry in your pocket or should it be something that carries you in its pocket? One thing I absolutely know,” he said aloud. ‘It should be bright!'”

Ray Bradbury’s short story, The Happiness Machine, published in 1957 predicted the modern day relationship between man and machine. The effects of social media on happiness, loneliness and connectedness are well documented; the results are worrying. Due to increased concern over how social media affects our well being, industry leaders are affirming their commitment to promoting community and togetherness. But, just how effective can this mission be? and why doesn’t The Happiness Machine work?

How to Make a Happiness Machine

Let’s appeal to the wisdom of another era, before smartphones entered our world. In The Happiness Machine, Bradbury tells the story of an inventor named Leo Auffmann and his wife, Lena Auffmann. Leo’s goal is to repair the relationship between man and machine by inventing a Happiness Machine. He investigates the pleasure of life and becomes consumed with the project.

Today, people are constantly in need of stimulation, entertainment, and pleasure. Digital platforms fulfill this need. However, after coming under scrutiny for negatively impacting lives and minds, Facebook developed research initiatives to examine and improve the way we use the platform. One could say their mission is similar to that of Leo Auffmann.

A Cautionary Tale

What is the problem with how platforms like Facebook fulfill the market need for pleasure and entertainment? In the story, when Leo’s wife, Lena, tries the machine, she sees and experiences the wonders of the world, she smells perfume and feels like she’s dancing. However, she is happy only for a time. To Leo’s confusion, Lena soon begins to cry harder and harder.

“Oh, it’s the saddest thing in the world!” she wailed. “I feel awful, terrible!” She climbed out through the door.

“First, there was Paris!”

“What’s wrong with Paris?” [Leo asked.]

“I never even thought of being in Paris in my life, but now you got me thinking: Paris! So suddenly I want to be in Paris and I know I’m not!”

In the NPR Podcast, Why Social Media Isn’t Always Very Social with Shankar Vedantam they expound upon why social media breeds unhappiness. Studies show higher levels of social isolation among social media users. As posited in the podcast, “…this might be because our online lives fail to match up with our real ones.” In the case study they used, the social media user was not only comparing herself to the the lives of her friends, but to the misrepresentation of her own life. Lena Auffmann felt something similar in The Happiness Machine.

“No, no! It’s not important. It shouldn’t be important. But your machine says it’s important! So I believe! It’ll be alright, Leo, after I cry some more.”

…

“Paris [I’ll] never see! Rome [I’ll] never visit.’ But I always knew that, so why tell me? Better to forget and make do, Leo, make do, eh?”

The Hedonic Treadmill

This story has a lot to say about happiness, how we seek it out, how we get it, and how we keep it. Lena’s experience was real in the moment, but once it was gone, she craved more. The hedonic treadmill theory posits that people will always return to a baseline level of happiness, regardless of what happens to them. In the story, Lena explains to her husband,

“Leo- how long can you look at a sunset? Who wants a sunset to last? So, after a while, who would notice? Better, for a minute or two, a sunset. After that, let’s have something else. People are like that, Leo. How could you forget?”

Pleasure and excitement, fulfilling moments real or lived vicariously through social media: all of these things were not made to last. The flaw of the Happiness Machine is its attempt to manufacture happiness forever. Human beings will always be left wanting more.

Should a Happiness Machine be Something You Can Carry in Your Pocket?

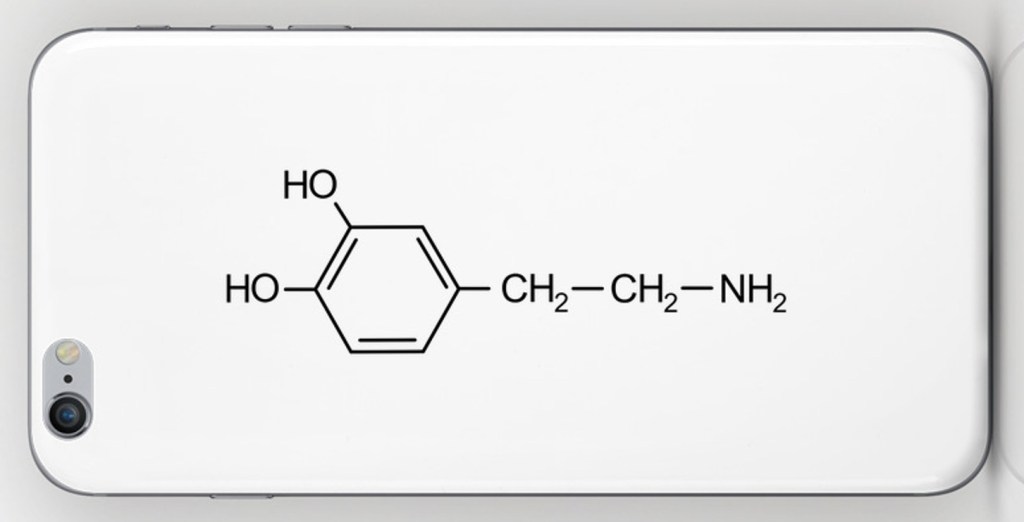

The effect that social media has on the release of dopamine in the brain is well researched. The user interface of sites like Facebook and Instagram are designed to reward the brain with little bits of dopamine- the neurotransmitter associated with pleasure. With the advent of smartphones, in conjunction with social media, we have invented Leo Auffmann’s Happiness Machine. The machine became not a method for happiness, but a requirement for it. Lena, explained in the story,

“I know only so long as this thing is here I’ll want to come out… and against [my] judgment sit in it and look at all those places so far away, and every time [I] will cry and be no fit family for you.”

Just as Lena desired to return to the machine against her better judgement, we constantly and mindlessly check our phones for another hit of dopamine.

How to Fix the Happiness Machine

At the end of Bradbury’s story, the machine catches on fire. Lena watches to make sure it burns down. Leo reflects on his mistake, and stares through the front window of his house. He realizes he’s looking at the real Happiness Machine: his family and his home.

This emphasis on social and community values echoes in Facebook’s initiative to inspire “active use” of the platform. While this is a worthy endeavor, could a private company like Facebook ever achieve this end when lack of happiness is good for business?

I think we should heed the wisdom of the past in order to cultivate a brighter future.

– How can we avoid the fate of the Auffmanns?

– What is the true Happiness Machine and could we ever get it to work?

– Will Mark Zuckerberg have better luck inventing the Happiness Machine?

– Are we already trapped in Leo Auffmanns’ Machine with smartphones and social media?

I believe Leo and Lena Auffmann know the answer.

This is a really interesting connection that you have made here. The whole idea that our social media is a “Happy Machine” is totally accurate in my mind. I always hear people discussing their love- hate relationship with social media because they feel addicted to it. The temporary happiness leads us wanting more, but also being more upset with the outcome of seeing peoples presentations of lives that seem better than our own. But other peoples as well as our own self reassurance keep us coming back for more. It becomes like a toxic relationship. It’s interesting to see if there will ever be a solution to this issue. How do we get people to realize what Leo Auffman came to realize when he found true happiness in his family and home? And do these big social media companies actually care about the well being and happiness of their users? Or do they realize that the addicting quality of these dopamine releases that their sites give is what keeps their company going? Do they actually just thrive off people’s temporary happiness?

LikeLiked by 1 person